By Blair Casey

Researchers in Australia have created a brain machine interface small enough to be implanted into the brain using a non-invasive procedure.

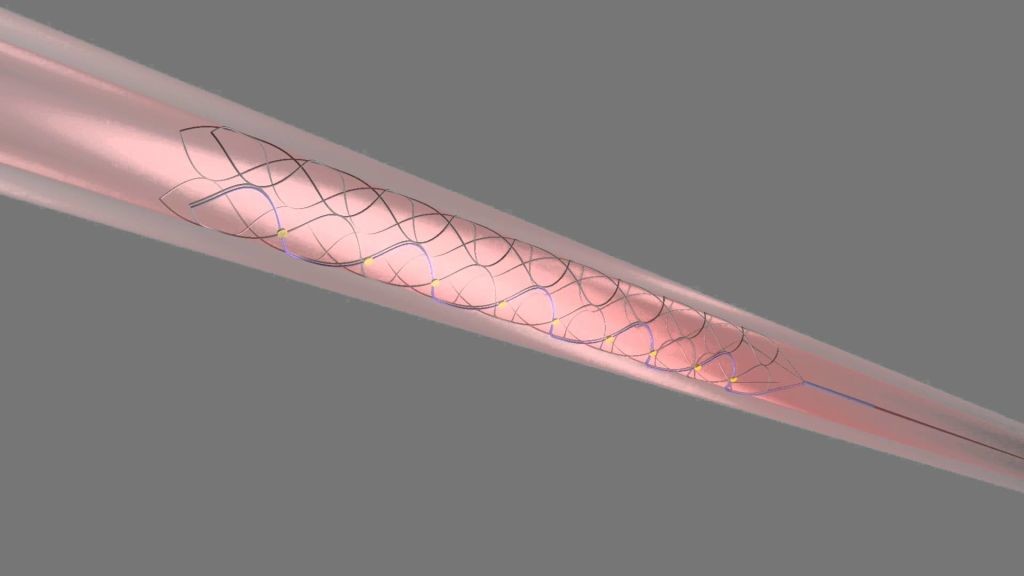

The stentrode, designed in Melbourne … will be inserted into the blood vessel with a catheter fed up through the groin – the same approach that has been used for years for cardiology and removing stroke clots.

Source

Designed to monitor and read signals from the motor cortex, the stent-based electrode, stendrode for short, decodes neural signals, re-framing the brain’s electricity into an algorithm that can be used to interact with bionic counterparts such as prosthetic limbs, wheelchairs, computers and (potentially) exoskeletons.

Although the stentrode has only gone through pre-clinical trials, people are already referring to the device as a “bionic spine.” The device is predicted to vastly improve the lives of those living with paralyzed and amputated limbs. Clinical trials are scheduled to begin next year.

TIMELINE

Harnessing the Power of Thought

2009: Pierpaolo Petruzziello, amputee, demonstrates the success of a bionic experiment in which he is able to move a prosthetic limb with “the power of thought” after a month of intensive practice.

Sant’Anna School of Advanced Studies

2012: Cathy Hutchinson, a quadriplegic uses an implanted BMI to control a bionic hand. She takes her first independent drink in ten years.

Brown University

2015: Les Baugh, a double amputee, test drives a pair of bionic prosthetic arms that have been customized for him through targeted muscle reinnervation surgery.

Applied Physics Laboratory at John Hopkins University

Stentrode: Designed for Life

Earlier variations of BMIs (See the above video of Cathy Hutchinson) required invasive brain surgery in which electrodes were placed directly on the brain to monitor and decode brain signals. In addition to requiring complex surgery, this early BMI hardware experienced wear and tear that eventually hampered communication between the implant and bionic counterparts.

In order to create a lasting, life-long solution, researchers and engineers from the University of Melbourne, the Royal Melbourne Hospital and the Florey Institute of Neuroscience and Mental Health looked to implants such as pacemakers for inspiration. Crafted from a flexible alloy called nitinol, the revolutionary stentrode device measures only three millimeters in length. Once inserted into the blood vessel, the device expands into a cigar-shaped basket. Tiny electrode discs record and transmit brain signals.

During pre-clinical trials, researchers discovered that the stentrode’s electrical signals became clearer and stronger after the device was absorbed into the vein wall, exciting news for those who feared the sound of rushing blood would weaken the electrical signals. The next challenge for merging man and machine will rest on the shoulders of those who are selected to participate in clinical trials.

Since the first breakthroughs in thought-controlled prosthetics, the amount of mental astuteness and perseverance of trial subjects has been key to success. In late 2017 carefully selected participants will be pioneering the next wave in bionic technology, synchronizing thought with electric limbs.

ADDITIONAL READING: